School of Rock [Music Photography]

With the possible exception of formula one driver or astronaut, no profession radiates glamour like that of a rock star. In the orbit of the rock star, the live music photographer appears, to many, to be a dream job. But, is everything as it seems? Paul Clark investigates.

Scene shifts

While there is still clearly work for photographers in the music scene, it has changed dramatically over the years, and not necessarily for the better. One factor is the decline in print magazines, formerly major customers for photographs of live music acts. Legendary performance photographer, Tony Mott says that the music photography industry, as it once was, has gone. “At one time, my work was going to 172 music magazines. Now, 171 don’t exist anymore,” he says. “I’m fortunate to have done what I did, when I did.”

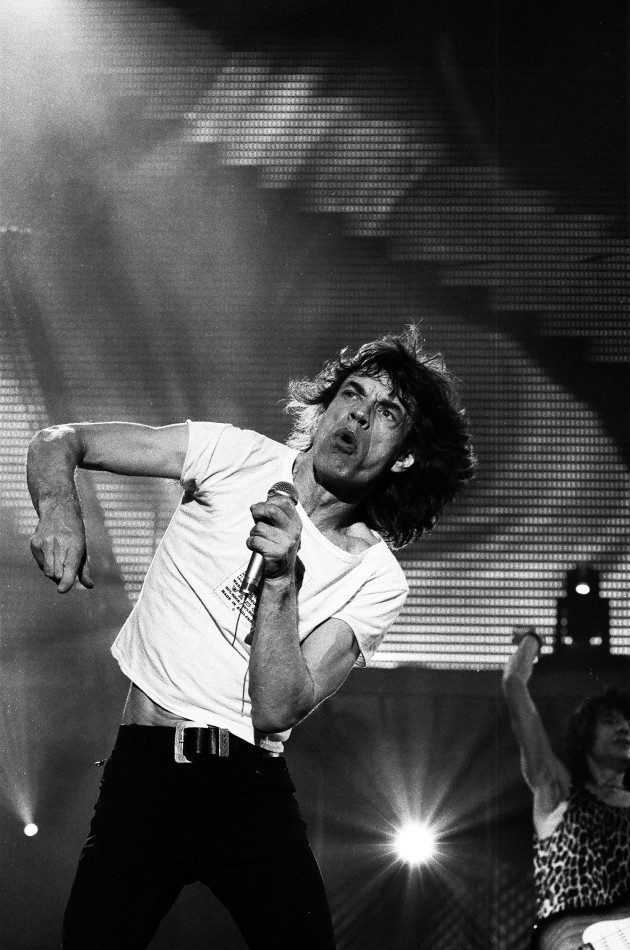

A second factor is that the grassroots live music scene, once a starting point for performance shooters, is not universally healthy. The grassroots live scene, Mott says, is an important stepping-stone for photographers to move on to the bigger concerts and tours. In Mott’s case, photographing the thriving music scene in 1980’s Sydney was the start of a career that led him from hotel chef to, among other assignments, tour photographer with The Rolling Stones, Fleetwood Mac and Bob Dylan.

The Power and the Passion

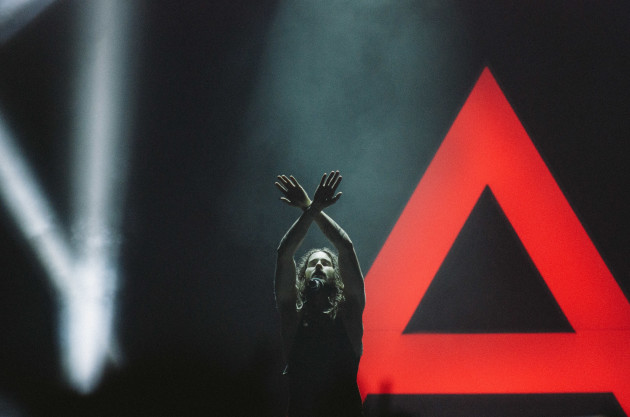

Successful music photographers seem to share two characteristics. One is a passion for music, and the other is that they started their careers close to home, with their local music scene. Mott is one photographer who did this. Vienna photographer, Matthias Hombauer is another. “I started out in small clubs,” he says. “I just went along and started taking pictures in the front row.” Hombauer also had some knowledge of how rock bands and the music scene worked, as a result of learning guitar and playing in a local rock group. Hombauer has a PhD in molecular biology, and photography was not his first career. It was a passion that, with his passion for music, set him on the road to his second career.

Perth photographer, Tanya Voltchanskaya also started ‘local’, shooting within a very close-knit music community in Western Australia. From the age of 16, she was shooting friends in bands, covering events, networking and sending photos off to potential clients. At first, it was all voluntary work, but later the paid assignments started to come in. “Slowly, I got my name out there [into the music industry],” says Voltchanskaya. “I was also working on music videos, which introduced me to more industry people.”

Getting technical

The challenges of live music photography are not really about the gear. Almost any photographer can find the necessary kit. Chicago photographer Tim Hiatt, whose long list of photo credits includes Robin Thicke, Avril Lavigne Echo and the Bunnymen, Iggy Pop, Motorhead, and Faith No More is happily shooting with a Nikon D700 with 70-200mm f/2.8 and 24-70mm f/2.8. “That’s pretty much all I need. I never really felt the need to acquire lots of new kit,” he says.

The more pressing issue is really achieving suitable access to get spectacular shots. Most of the accredited photographers are given time, or three, or only two songs, in a restricted pen. “All the photographers are squashed into one little area and then [after the allocated songs] we get escorted out. You might end up getting only a song and a half.” At one festival, Voltchanskaya was asked not to shoot the ‘scheduled’ songs as it was still light and the band wanted to be photographed at night. The photographers all dutifully waited for night to shoot the set, at which time all the technology failed and plunged the stage into absolute darkness. “I got some cool shots, eventually,” she says.

Network your way in

Hombauer, who has developed professional relationships with artists such as The Prodigy and Fink, emphasises the importance of meeting the right people in order to develop access. “When a relationship develops [with a band], you’re not restricted to ‘shoot for three songs’. That’s when you can shoot on stage for the whole concert,” says Hombauer. In a similar vein, in 1992 Mott established a relationship with Big Day Out promoter, Ken West which facilitated a professional rapport with bands that continues to the present day.

Developing the rapport, and longer-term relationship with artists and management, is how photographers are able to build their portfolio to include other music industry work. That work includes providing images for album covers, shooting studio portraits of the artists, or covering complete tours.

Stand your ground

For those photographers working in and around the music industry, image rights and contracts are a significant issue. Two recent and widely reported examples of artists, or their management, proposing onerous contractual restrictions involved international acts, Foo Fighters and Taylor Swift.

In the case of Foo Fighters, as reported by the Washington City Paper, who were to photograph the band’s American Independence Day show in 2015, photographers were requested to sign a contract which assigned all image rights to the band in perpetuity. Furthermore, publication of any photos was subject to the band’s approval.

At around the same time in 2015, a leaked Taylor Swift contract was criticised for attempting to limit the use photographers could make of images shot, by requiring the approval of Swift’s management. The artist, however, was free to use the images for any ‘non-commercial’ purpose in perpetuity. Entertainingly, a further clause in the contract apparently authorised Swift’s management to destroy image recording devices and eject non-compliant photographers from the venue. It was not clear whether the ejection or the destruction would come first.

Hombauer says that he believes there has been significant push back against such one-sided contracts. “Those sorts of contract bring nothing to the photographer,” he says. “In some cases, the media have united against these rights-grabbing contracts. Mostly, the band will drop the conditions.” Reporting in the latter part of 2015 supports Hombauer’s statement. Québec newspaper, Le Soleil famously sent artist Francis Desharnais to sketch the Foo Fighters at the Festival d’été de Québec, an outdoor concert, while a Le Soleil news photographer shot from outside the media enclosure.

In Washington, Steve Cavendish, editor of the Washington City Paper, confirms that the paper did not sign the Foo Fighters contract for the 2015 Independence Day concert, instead offering to pay fans for pictures. “We got quite a number of photos from fans and published a few of them – and compensated the photographers,” says Cavendish. “The band’s management company didn’t comment to us and I’m sure the band itself never saw much about this: they pay people to handle this for them,” he says.

Cavendish thinks the issue for the bands is protection of their image, rather than holding any special dislike for photographers. “I think most bands and their managers, when you put the question to them, don’t want to be seen as either restricting another creative – like a photographer – or the press,” he says. “Most of them are just trying to make sure that their image doesn’t wind up in some commercial setting that they can’t control. I get that. We’ve happily added stipulations that protect against it.”

Since mid-2015, perhaps the dust has begun to settle a little. “We’ve had some restrictive contracts come our way since [mid-2015],” says Cavendish. “When we pushed back, almost all of the big acts altered them,” he says.

Check the fine print

Hiatt is careful to point out that image rights are not always an issue. “A lot of the contractual issues depend on who you’re shooting for,” he says. Hiatt is an experienced professional who has shot for Rolling Stone, MTV, and many other clients, and is syndicated internationally through Getty Images. “If I’m presented with a restrictive contract, I won’t sign. I’ll try to tweak it a bit,” he says. Hiatt speculates that contract negotiations may be harder for emerging professionals. “If you’re an up and comer,” he says, “it depends on how well you sweet talk ‘em.”

Hombauer agrees. “Even the big bands don’t have contracts every time,” he says. It seems that it also pays to read the fine print, even if you have shot a band before. “When they do have a contract,” says Hombauer, “it’s not always the same as the last time.”

A long way to the top

If it’s a long way to the top if you want to rock and roll – with thanks to AC/DC for their lyrics – the journey is almost as far for photographers who want to capture the journey with pixels. There are some demands that may be considered slightly peculiar to live music photography, such as the extended tour or the music festival, but generally the pressures on music photographers are common across the industry as a whole.

The Internet and social media is the classic double-edged sword. In common with other professional photographers, music photographers benefit from the power of the Internet, especially social media, for marketing. They also suffer, as others do, from the general decline of print media and the consequent loss of photo sale opportunities. The ability of social media to provide amateur photographers – and crowds with smartphones – with an outlet for their pictures further increases the pressure on music photographers.

None of this means the music sector has disappeared, only that those photographers who have diverse income streams are in the best position. “I don’t think I’ve ever been reliant on only one source of income, [via music photography],” says Mott. “It’s hard to believe that anyone is, and that’s not going to change.” Hiatt agrees. “I fit the music photography in with everything else,” he says. “Music is maybe 20% of what I do.”

Got the Keys to the Kingdom, Baby

The keys to success with music photography are broadly the same as professional photographers in other disciplines might list. There are, however, some subtle pitfalls related to the perceived glamour of the music industry. For example, amateur photographers covering a performance may feel honoured to be asked for their work. “Some people are shooting bands for a hobby and they will give away their work,” says Hombauer. “Professionals need to raise awareness of the issue and not give images to bands or management for free.”

So what should the aspiring pro music shooter do? The answer is not surprising. Shoot well, network well, and get your work out there. These days, it is barely worth mentioning that photographers need an awesome website. Sometimes forgotten is the key piece of advice: be good to work with. Hiatt sums it up succinctly: “You can be a great photographer, but people won’t want to work with you if you’re a massive dick.”

So, given the prospect of long hours crammed into tiny pens to shoot gyrating artists in limited time, is it all worth it? Hombauer, for one, insists that it is. He maintains that shooting music professionally is an achievable dream. “The whole process took about eight years to get to where I am now,” he says. “Sometimes I think, ‘What if I had started 10 years earlier?’ but it is how it is, and I’m here now.”