How photobooks can boost your business

Once upon a time, having your photobook published was something only a few, usually already famous, photographers were able to accomplish. The evolution of self-publishing – and in particular, the advent and growth of D-I-Y self-publishing – has changed that considerably. So now there are options. But the reasons to be published haven’t changed. And they might surprise you. Candide McDonald reports.

Producing a great photobook can be expensive, unless it’s published for you, but getting your work and your name out there, which for many photographers is the ultimate aim of a photobook, is achievable now for very many. And the expense of producing a photobook, in that case, becomes a business investment. Achieving the traditional aim of book publishing, to make money by selling your book, has never been easy, and still isn’t. D-I-Y marketing is another investment, and a complex undertaking. Book marketing isn’t easy for professional publishers either. But great books become good sellers every day throughout the world.

A great photobook

What makes a great photobook? Katrin Koenning’s Astres Noirs (created with Sarker Protick), won the Momento Pro Australian Photobook of the Year Award 2016. It was also named in the top photobooks of the year by several publications, including Time, The Guardian, and Lens Culture. “I need to love the work that is in the book, and there are of course a thousand different reasons for loving a work,” Koenning says. “I look to the work first, and then the other elements of the book. There are poorly designed books to which I return all the time because I never stop learning about, or losing myself in, the great work. Then there are very well designed books in which the work doesn’t touch me, so I’m not the right audience for that book. Generally, an elegance and clarity of design that helps the work sing on the page, but acknowledges the presence of the work as the main element, is magic.”

What makes for a successful photobook is simpler for publisher, Haru Sameshima, of Rim Books New Zealand. “It’s having something to say that has not been said before, about something or somewhere or some people. It’s a personal vision and/or story, conveyed in a well-conceived package as a book.”

A photobook creator has to be aware that he or she doesn’t have just one audience judging “greatness”. Libby Jeffery, marketing manager at Momento Pro, which supports self-publishers through production and marketing, comments, “A critical reader – judge, reviewer, academic, curator – might look for photographic excellence, a strong visual narrative, sophisticated design, and appropriate integration of text, while a retailer or distributor might be interested in a specific photographic genre, a stand-out cover, interesting binding, or artistic packaging. Members of the public, in a bookstore, at a trade show, or exhibition might be more interested, however, in content that has popular appeal – visual humour, animals, or exotic destinations – as books that play with intangible concepts, a creative process, or present a visual representation of a criminal case might leave them feeling cold.”

And not all great books are successful ventures for the photographer. For Simon Devitt, who self-published the New Zealand Photobook of the Year 2016, “personal success is making the photobook you wanted to make, the vision you had becoming a real, working object.” While for Sam Harris, creator of The Middle Of Somewhere, published by Ceiba, it’s a very personal thing. “Did I achieve what I had in my mind’s eye? Does the finished book fulfil my intentions? Does it convey my intended message? Does it take the viewer into an immersive experience? Does it stir the soul? If so, then for me, it’s a success,” Harris says. For both Devitt and Harris, if their books are selected for exhibitions or awards, or even win something, that’s a bonus, but it’s not the primary aim of the exercise. However, a book that sells well helps to recoup costs and is a sign of a healthy relationship between the photographer and their audience.

For a publisher, the success of a photobook “totally depends on the purpose of the book,” Jeffery says. “If it meets its intended purpose, it is successful. There are so many different reasons for creating a photobook project, including: to record a personal story, to explore a place, space, issue or creative process; to create a document for historical preservation; to produce a book for mass distribution and major revenue; to raise your professional profile and make your photography more accessible; to support an exhibition; for collection by cultural institutions; to showcase your life’s work; or to generate awareness or inspire action,” she says.

Money is no objective

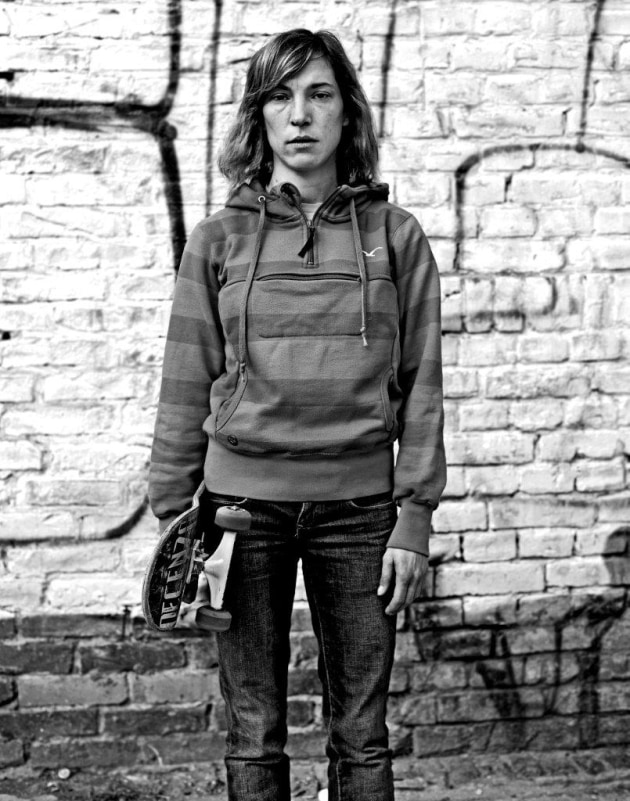

Making money is always in the back of every book creators mind, but it is rarely a top motivation or goal. Robert van Koesveld, creator of Geiko & Maiko of Kyoto, says that he’s never had any illusions about making money from publishing. “You would need to sell out multiple print runs to make a profit if you include your time and all other costs. Still covering the printing and freight costs through crowdfunding removes a big sting.” Nikki Toole, whose book Skater was published by Kehrer Verlag, quips, “One publisher friend told me that art books no longer make money unless the artists is famous or it has cats on it.”

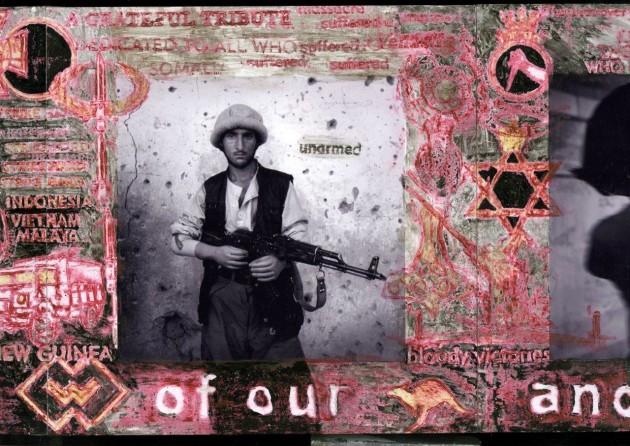

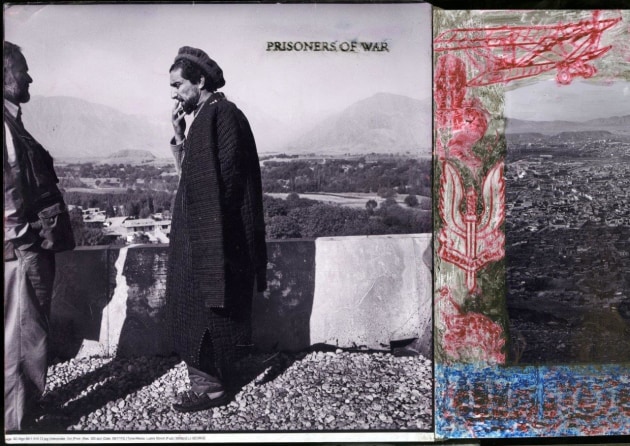

Some seasoned photobook makers have learned to overcome the problem. Stephen Dupont, Jeffery comments, has developed a unique way to make his photobooks viable. Dupont has been published by major international trade publishers, which print editions in the thousands, and has also worked with smaller independent publishers who produce only hundreds of books, but with premium quality materials for a premium market. But in recent years, he has moved toward fine art, limited editions, preferring to produce inkjet-printed, archival limited editions of 1-5 copies that sell for thousands of dollars to public institutions and private art collectors. He only needs to sell a few to make a reasonable return and fund his next project, rather than spend months selling hundreds that make a few dollars after the publisher and retailer cut.

So, if making money is not the light at the end of a very long tunnel, what is? “A book is a wonderfully portable, easily dispersed way of getting your work out there,” states Helen Frajman. And that is the niche that Frajman, director of M33, has carved out.

The portable exhibition

Frajman’s artists tend not to have making money as their main game anyway. “Their aim is to have their work seen, often internationally, but also all round Australia,” she says. “That’s something a book can do much more quickly, cheaply, and effectively than an exhibition. And it’s much more reliable than word of mouth.

“One of our artists has just had five pieces purchased by the National Gallery in Canberra because of work seen in their art book. And even though that book was funded by a grant, at between $16,000 and $25,000 to make a quality art book, it wouldn’t have made money. It was an investment in the artist’s career, and it paid off,” Frajman says. “We’ve also just sold ten books to the National Library in Canberra.”

But if all of that sounds terribly discouraging to you, there are photobook money-makers out there. Craig Wetjen, who published Men and Their Sheds last year with Echo Publishing in Melbourne, had an incredibly successful sales experience, received massive publicity – and also raised the profile of men’s mental health, which has potentially earned him a spin-off TV show and a new publishing deal.

Having your book published, which means losing some, or all control of the process, depending on the publisher, can be daunting for some. M33 softens this blow by taking a very collaborative approach to creating the books it publishes. Many of the books are co-published, so the photographer has a financial stake in the undertaking, but Frajman likes the process to be as organic as possible. She only has one rule: “People do judge a book by its cover.” She likes to have a big say in that, but everything else is worked by the designer, the artist, and herself more or less equally.

D-I-Y?

Still many photographers opt to – or have to – self-publish. Getting published is achieved by only a small percentage of authors who submit a manuscript or idea, and major trade publishers consider photography to be a very niche market. “Trade publishing, mostly, appears to be driven by bottom lines and a marketing plan, rather than by the content of idea, or the story,” Devitt says. “It’s so much more accessible now to create exactly what you want to create without the need of a traditional publishing engine. [Publishers] often provide significant distribution, but only for those books that ‘have to’ sell. So, it may mean producing smaller numbers sometimes, but I think if you have an idea or vision to make a photo-book, make it!”

And the cost can be shared, now that crowdfunding has become an accepted phenomenon. UK fine art photographer, Kirsty Mitchell raised £335k in crowdfunding for her self-published book, Wonderland. In Australia, Calley Bena Gibson raised $107k for her homeless dogs fundraising photobook, Life of Pikelet. Of course, these are maximum funds raised, but it does show that crowdfunding a publication is viable. But any photobook self-publisher must go into the project knowing that distribution is the biggest hurdle for self-publishers – as well as independent publishers. There are very few distributors in Australia.

Sam Harris summarises the options from experience. “Trade publishing means a chance at better distribution because the publisher will not support a project without realistic sales prospects. It can mean access to good designers as well. Self-publishing gives you full artistic control, but greater financial risk if you print commercially. Crowdfunding gives you a way of measuring demand and underwriting the heavy cost of printing. However, small run, low quantity/high quality, high cost, ‘Limited Edition’ is a pathway I may use for some future projects.”

Look and feel

If you decide to self-publish, then you’re in charge of your book’s look and feel. This feels like a creative freedom, but producing a book has a strong rational underpinning. Jeffery explains: “Size and format are becoming very important considerations as the cost of shipping increases. It is almost prohibitive from Australia as shipping can equate to the cost of the book in some cases! Smaller, lighter books allow for cheaper international distribution, but it may not suit the purpose of your book. If you’re only distributing locally, in high-end bookstore, art galleries, or designer fashion or gift stores, a larger book with thicker paper, packaged in a striking slipcase or box might be more suitable.

“The size, cover, and material of a book needs to be appropriate to the purpose of the book. If the book tells an intimate, personal story through dramatic black and white photographs, for example, then an A3 size book with bold colours and a large metallic emboss design on the cover seems inappropriate. An A5 size book, with a soft, tactile, understated cover with a single inset photo that captures the essence of the book would be more complementary,” says Jeffery.

And there’s cost versus appearance to balance. If you self-publish, that balance is entirely up to you. If you co-publish, you will have a say. “Make the most beautiful book you can make for your budget, not the most books you can make,” is Frajman’s advice. She also knows it takes some expertise to design a beautiful book, so her corollary is, “find the best publisher or the best designer you can for your budget. Don’t skimp on that.”

Is a photobook worth it? No photobook creator in this article said no. “The two photobooks I’ve personally published of my own took seven and two years, respectively, to produce. Two books in nearly ten years is pretty bloody minded! You have to have an obsession to create the thing you want to make, and with as few compromises as possible.” But Louise Hawson, creator of 52 Suburbs and 52 Suburbs Around the World, says, it’s “for love! That was my reason anyway. I wanted to give my blog followers a permanent reminder of the experience we shared online for over a year. And I wanted to ensure my daughter, who featured in the project, had a beautiful book that she could share with her children one day.”

Contacts

Simon Devitt

Stephen Dupont

Sam Harris

Louise Hawson

Katrin Koenning

Nikki Toole

Robert van Koesveld

Craig Wetjen

M33

Momento Pro

Rim Books