How to protect your IP

In the face of the widespread theft of their images, many photographers feel as if the battle for intellectual property rights has been all but lost. The odds are overwhelming, and even for the valiant, there remains but a small arsenal of weapons. Armani Nimerawi explores what to do when the worst happens and what options photographers have to protect their work.

The art of stealing art is as old as art itself. What is believed to be the first recorded case of intellectual property (IP) theft was immortalised in a poem by the famed Roman poet Martial in 85 BCE, who accuses a fellow poet Fidentinus of reciting his works without credit. “If you are willing to have the poems called mine, I will send them to you for free,” writes Martial, “but if you wish them to be called yours, buy my disclaimer of them.”

Though poetic verse has become a less popular means of delivery, the warning in Martial’s poem is one many contemporary photographers would find painfully familiar as they struggle to convince the world of their most basic right to be duly credited, and paid, for their work.

The impact of IP theft is wide reaching and is often to the mortification of more than just the photographer. Fashion and editorial photographer, Peter Coulson, has had his images used to advertise ‘pay for use’ sites, with the faces of models he’s worked with appearing above the caption, “If you want to see more, pay $2.50 and click here.” “They’re not showing more of that girl but are using her picture to get people in,” says Coulson in disgust.

Anti-social media

Though Martial’s epigraph reveals the long history of IP theft, it exists today on a scale hitherto unseen, as creatives have struggled to enforce IP laws in the rapidly changing digital arena. Though efforts have been made to develop technologies to prevent violations, using technology to mitigate the risk has proven almost impossible, as infringers have so far managed stay one step ahead. Traditional methods such as watermarking are now almost redundant. Not only are they easily removed, but most photographers feel as if their use compromises the quality of an image.

Where there’s a will, there is indeed a way, and the will most definitely exists. The freedom of information offered by the Internet has spawned a generation of ‘remixers’ and disciples of ‘Free Culture’ who believe that rather than protecting creativity, the concept of IP in fact smothers it. According to their manifesto, all creative works should be freely distributed and modified without penalty. Remixers aren’t just confined to the world of rap, torrent downloaders and fan-made YouTube videos. American artist and ‘re-photographer’ Richard Prince, has made a handsome living off appropriating the work of photographers and using them in his pieces, sometimes unaltered, since the mid-1970s.

The rise of social media has only served to exasperate the situation by facilitating the unrestricted stealing and sharing of images, while simultaneously offering photographers an invaluable platform to share their work. It’s the ultimate Catch-22: you either have a presence online and resign yourself to a certain level of infringement, or you don’t.

It was the tension between these two options that led to one of the most prominent IP cases of this century: Morel vs. AFP and Getty. A David and Goliath story that gripped the photographic community, the case centred around the sourcing of eight images from the newly-created TwitterPic account of Haitian-born photojournalist Daniel Morel, who uploaded his images just minutes after a 7.0 magnitude earthquake hit Haiti in 2010.

For Morel, social media represented a means with which to distribute and sell his images on his own, thus avoiding losing more than half of his fees to an agency. “When you’re in a danger zone, you risk your life to take a photo and then they sell it and they give you nothing. What is this?” asks Morel incredulously. “That’s what was in my head going into the earthquake. I didn’t want to risk my life just to lose 70 per cent of my money.”

Unfortunately for Morel, Agence France-Presse (AFP) and Getty Images had helped themselves without asking his permission. A total of eight of Morel’s images were sourced from his TwitPic account and distributed around the world, initially attributing the works to another photographer. Though he’d experienced infringements in the past, never did he expect that his images would be stolen and published by one of the three largest news agencies in the world. “When I was in Haiti in the 90s, local papers would ‘steal’ my work, but when I sent them a letter telling them to not do it again they never did,” says Morel. “I never thought a company like the AFP would do such a thing.” The theft sparked a three-year legal battle that would eventually see a jury award Morel $1.22 million in damages, and led many photographers to question their own presence on social media.

An education

It’s obvious that social media comes with inherent risks, and there’s no working around the fact that technology can offer very little help when it comes to mitigating the risk of IP theft. Still, photographers have accepted these risks and continue to choose to post their images online rather than be left out of the virtual marketplace. “I think that’s part of what happens when you put something on the Internet,” says Swedish photographer and retouch artist Erik Johansson. “It’s part of this game – people can steal it and you have to be aware of that.”

However, the theft of images does not always take place online. Often, IP violations originate when a client fails to respect basic licensing agreements. Luckily, this type of violation can be easily anticipated and prevented through client education. Communicate to clients early on what the licensing terms are – the region, the period of use and specific use/s permitted – and then follow up just prior to expiry of the rights licensed.

This has been a strategy wedding photographer Daniel Griffiths has employed over the last 12 months, and to great effect. Griffiths will clearly state his licensing terms in his initial service agreement, which is received a year or 18 months before the wedding, and then again in the first sneak-peak email after the wedding. “I remind them that commercial copyright still applies,” he says. “That is, if the dressmaker, make-up artist, florist or venue wants to use any of these images, they must contact me first. They are free to use them for their own personal printing and distribution to family, friends, Facebook whatever, but commercial copyright still applies.”

Infringement, where art thou?

If your best efforts to mitigate are all for nought and your IP is infringed upon, before taking action, you must first know that the infringement has taken place. Reverse image searches, such as those offered by Google and TinEye, promise to track where an image appears online, what sizes it appears in, and instances where it’s been modified. TinEye offers plug-ins for all major Internet browsers.

While reverse image searches are a popular option, many photographers have reported mixed results with reverse image searches. “Most of them don’t actually work very well,” says advertising photographer Julian Watt. “I’ve done searches for fairly strong images of mine and what comes up in those sorts of searches is just a lot of similar backgrounds or the like. It’s hardly useful.”

This is what led Australian software engineer, Matthew Johnson, to found Image Witness. Unlike other reverse image search engines, Image Witness allows photographers to track entire libraries on an ongoing basis, with monthly report cards showing where images appear, even images that have been cropped or added to. Working on a subscription basis, with the cost of plans depending on the number of images in your catalogue, Image Witness uses matching technology that Johnson believes has very few limitations. “The image matching technologies we leverage are incredibly effective,” he says. “The only time you will struggle with results if you have an image with almost no content in it.”

If you’re not up for hunting and gathering evidence of copyright infringement yourself, a number of enterprising Americans have established businesses that will do it for you. The US-based Copyright Services International (CSI), Image rights recovery, and the apparent avengers of the IP world, the Copyright Defence League (CDL), will, for a fee, chase down your images for you, and coerce infringers to settle out of court with the threat of legal action.

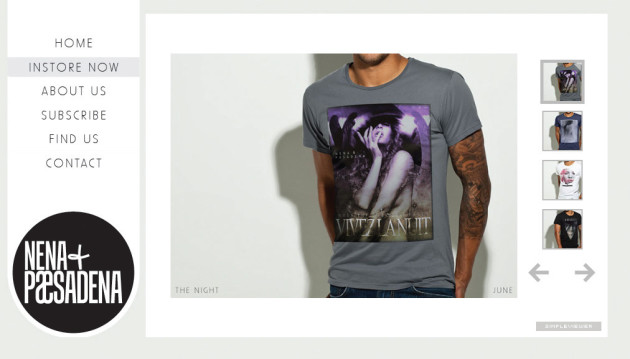

Another way photographers are keeping track of their images is through their fan bases on social media sites, ironically the very medium that has made IP theft so much simpler. This was certainly the experience of digital retoucher and visual artist Harmony Nicholas, whose image Colour Me Kelley was stolen by a manufacturing company in Thailand and reproduced on t-shirts and singlets sold around the world. “There was a period of time where I was getting several messages a day on Facebook informing me of the t-shirts; people who had seen them in shops, in market places, in Thailand, even on people,” says Nicholas. “It’s like having a global spy network.”

More flies with honey

If you do discover an infringement has taken place, the recommended course of action is to contact the infringers and alert them to the violation in a polite manner, or as polite as is possible. Though photographers are aware of their rights, there remains a great ignorance of IP in the general public and it’s never safe to assume that a violation has taken place knowingly or deliberately.

This is the approached taken by Watt, Griffiths and Johansson. “Either I don’t really hear from them and then it’s down, or they get back to me and say, ‘Oh, I didn’t know. I thought it was OK!’” says Johansson.

Though this type of response seems the norm, it certainly cannot be considered the rule. Some infringers will simply turn a deaf ear and then disappear into the ether, as was the experience of Trent Mitchell, whose images were used in a Facebook Page Manager App and branded with someone’s logo, all without his consent or payment. After initially contacting them to alert them to the violation, Mitchell heard nothing. “That was one of the major things that shocked me about the whole thing. There was absolutely no communication with myself, and I may have been happy to negotiate something.” Eventually, Mitchell received a settlement offer from a pro-bono lawyer. “They offered me, well, I don’t even want to repeat what they offered,” he says. “It was a kick of dirt in the face. Yet the fee was nothing. A high-school student could afford it!”

The frustration experienced after receiving such responses echoes Griffiths’ exasperation at having to be polite to someone who has just stolen his images. The frustration experienced after receiving such responses has led many photographers to eschew the polite approach and go straight for the jugular. “What I do – and it might seem a bit cruel – is I just name and shame,” says wedding photographer Jonas Peterson, who has experienced IP theft first hand. “I have such a huge following so if I put it on social media that this person is stealing, the first thing that happens is that they get a lot of e-mails and comments and it just goes out in the limelight straight away. It’s just to scare people off from doing it. That’s my reasoning. And it’s always happening. It’s never them. They blame it on someone else. They always have an excuse.”

Photographers should beware however, as such tactics can easily get out of hand. This was the experience of Nicholas, who used to expose infringers online before experiencing its potential to incur what she describes as a “lynch-mob effect” “In the end, I found it was doing more harm than good,” she says. “When I started receiving messages from people proudly boasting that they’d stopped some poor unsuspecting person in the street who happened to be wearing one of the t-shirts and giving them absolute hell, I knew it had gone too far.”

In fact, the heavy handedness of photographers seeking out IP violators has led to the creation of sites such as ExtortionLetterInfo (ELI), which reverse the naming and shaming paradigm, and expose those photographers (or stock agencies) that they deem to be too aggressive and unreasonable in their “extortionist” requests for money.

Lock and load

If you have exhausted all polite avenues of communication and the infringers refuse to surrender, then taking legal action is an option, though it is an avenue pursued by few. There is due to the widely-held belief that this course of action is not one that will see justice served. “It’s not a misconception,” says Chris Finn, principal partner of Finn Roache Lawyers, experts in IP law. “The problem is that with most intellectual property infringements, you have to deal with Supreme Courts or the Federal Court of Australia. That, in itself, is a very expensive jurisdiction.”

Many Australian photographers are now registering their work with the U.S. Copyright Office as the best means of protecting their content. This entitles photographers to pursue legal action in the US courts, and those who have registered works before an infringement takes place are eligible for damages. However, the process can be arduous and very expensive so it’s not an option for all.

Finn believes that Australia may benefit from the type of small claims courts established in the United Kingdom that offer a cheaper forum to hearing out cases relating to copyright infringement. It’s a model the US is also looking into in an attempt to free their Federal court system from the backlog of copyright claims.

A crucial part of ensuring your success in court is the evidence that you can provide, so ensuring you insist on written agreements and keeping them up to date is paramount. “I’m still amazed that there are people out there that will do jobs based on a verbal discussion,” says Watt. “If you’ve got no agreement, you’ve got nothing to stand on. It really makes it difficult to prove your case.”

If you do decide to go to court, know that though it won’t be easy, it can be done. “I thought it was going to be easy!” laughs Morel, “Because when somebody steals something, there’s no other way it can go - they are guilty. But I don’t regret it, because it’s about time that they have respect for local photographers. They treat us like the lowest in the scale. But even now, without local photographer no one would know what’s going on anywhere in the world. I hope photographers will start to think that it’s not impossible now. I hope most photographer will think ‘If he can do it, then I can do it.’” ?

Contacts

Peter Coulson www.koukei.com.au

Chris Finn www.finns.com.au

Daniel Griffiths www.dgphotos.com.au

Erik Johansson erikjohanssonphoto.com

Trent Mitchell www.tmphoto.com.au

Daniel Morel www.photomorel.com

Harmony Nicholas www.dalaiharma.carbonmade.com

Jonas Peterson www.jonaspeterson.com

Julian Watt www.julianwatt.com

Copyright Agency www.copyright.com.au

Image Witness www.imagewitness.com