The future of fashion photography

In the last few years, fashion has been forced to face a world in which the things it has never much cared about have become very important to the people on which it depends – consumers. The images with which it presents itself, where they are seen, and how they are created, has had to adapt. Fashion photographers have had to adapt too. Candide McDonald reveals the changing landscape.

2018 was a watershed year for fashion. The veil was pulled off its ugly side by Dolce & Gabbana founder, Stefano Gabbana’s racist rants, Me Too’s outing of fashion photography legends, Mario Testino and Bruce Weber, for sexual misconduct, and public outcry about its disregard for ethical and sustainable production practices. According to global fashion search platform, Lyst, searches for ethical fashion surged by 47% in 2018. Fashion’s recent struggles are no more apparent than in Australia. Famous labels, Collette Dinnigan, Wayne Cooper, Alannah Hill, Jayson Brunsdon, Sass & Bide, Ksubi, Morrissey Edmiston, Charlie Brown, and Lisa Ho, have died.

How fashion is seen, advertised, and bought has also changed. For younger generations, digital comes first. Fashion accounts for 27% of online purchasing globally, according to a 2018 Forrester report. 266 of the top 1,000 online retailers are clothing brands, and across 32 countries the percentage of people who bought online grew during 2018 to 58% – half of them in fashion retail. 65% of the online fashion traffic is now done on mobile. And according to international consulting group, BCG, 57% of fashion advertising is now online. In fashion editorial, Cosmopolitan closed in Australia in December 2018 following a readership decline across three years. Only Vogue Australia (+11.8%) and Marie Claire (+3.1%) increased their readerships significantly throughout 2018, according to Roy Morgan data.

According to US fashion photographer Lindsay Adler, “The fashion and beauty industry has really pushed back against itself in recent years and split into two distinct aesthetic approaches – fantasy and authenticity. Fantasy is all about perfection and idealised beauty standards – the perfect skin, perfect clothing, perfect models. Authenticity is all about embracing the individual and what makes someone unique, perhaps in the way that they break traditional beauty expectations. This is why you see models with unique features, curvier bodies, and unusual skin more in a lot of recent campaigns,” Adler says. “The thought process is that many consumers want to see themselves represented in the campaigns and visuals by the companies they purchase from. The other side seeks to create imagery more about art and fantasy, rather than reality.”

More, please

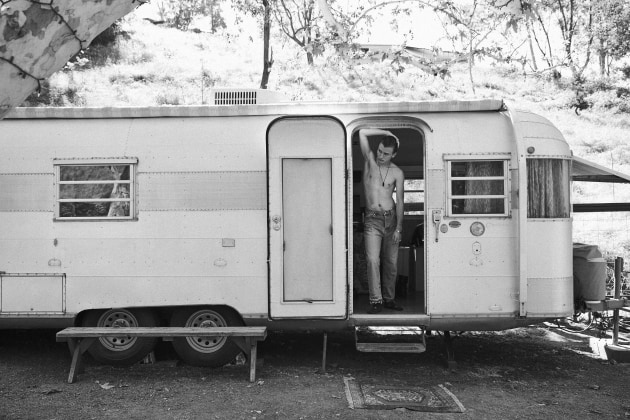

Australian photographer Luke Dubbelde has also observed a transformation. “Fashion photography has evolved a lot over the last decade, since the beginning of my career, and it still constantly is. The introduction of social media and the digital age in general have definitely caused huge changes and have given artists a platform with which to share their work with the world and the opportunity to build an audience to engage with. I think being a great fashion photographer now is someone who has something to say and is creating imagery that is authentic.” Melbourne-based photographer, Tintin Hedberg adds, “With editorial, advertising, and commerce moving online, the pace has rapidly increased over the past decade – both in turnaround time and the way we shoot. In many cases, the creative direction has shifted from highly polished and stylised to lo-fi, and we are shooting more frequently on location, rather than the studio.”

Trevor King, has noticed the same trend. “Commercial and editorial clients have less money to spend on shoots these days, but they are shooting more often. I used to shoot for the same client two to four times a year for each seasonal release. Now, they shoot eight to twelve times a year. They need more imagery and content for their social media channels. The more, the better, and when a shoot is shot, they more or less need the imagery ASAP to be released the following month. It used to be released in three months.”

“Ten years ago, there was only a handful of magazines in Australia, so you would only see a select few photographers’ work when the magazines came out,” King adds. “Now, there are hundreds of online platforms where photographers from around the world can submit stories. We used to have magazine editors hiring their choice of what they thought were the best photographers in town. Now, we just get flooded with excessive amounts of imagery from whoever is online that has not been curated by anyone.” Hedberg comments, “Social media has been a complete game-changer. The number of shots per day has increased significantly and it is very rare that a photographer is given the time and resources to craft images to perfection. Therefore, those who can shoot fast and create quality images within a limited time will come out on top in this change.”

With social media has come the influencer phenomenon. Fashion influencers are often celebrities. This has always been so, but now they have platforms where they can churn out their images themselves to hundreds of thousands of followers who hang off everything they say, do, and wear. “Everyday” influencers are new, a product of social media. Brands turned to them in droves initially to disguise the marketing nature of their images. That is waning, both because people are becoming savvy to the practice, and influencers are being controlled somewhat by social media algorithms.

Fashion and commercial photographer Ren Pidgeon is unimpressed with influencers nonetheless. “I don’t think they really play a role in fashion photography. They have their own scene. It’s like a different industry with its own style – influencer in front of wall, influencer in front of nice gate walking, et cetera, et cetera. It’s not fashion photography.” Pidgeon adds that most editorials are published online now. “When I shoot editorials that are self-commissioned, I want them out as soon as possible, so I will usually send them to online mags that can have them out instantly.” Self-commissioned photography is a trend noted, too, by Australian fashion designer, Gary Bigeni. “Photographers are teaming up with make-up artists and stylists and creating spec work in vast amounts,” he comments.

Much of the speculative print work is being picked up by independent publishers. “There are many independently published magazines out there in the world for young photographers to do their best with the intention of being published,” notes Australian fashion photographer, Michele Aboud. “You don’t get paid, but you do get the free publicity with your name on the page, and this currency can translate into shooting advertising campaigns.”

For the world’s sake

Increasingly, fashion images are shot not just to be pictures promoting the latest looks, but to integrate fashion into a cultural context, in both editorial and advertising. “The shooting style now is very anti-fashion. The rules set for decades are being bent,” Aboud explains. “The aim is no longer to create a pretty or powerful image. It has a need to say something more, be a commentary that is there to attract and invite thought or conversation.” This is exemplified in Diesel’s Unfollow campaign this year, which applauded individuality. The fashion ideal is no longer perfection either. Themes of imperfection and difference prevail. Dior’s dreadlocked Indira Scott, Chanel’s Sudanese Adut Akech Bior, and Versace’s “longest-ever advertising image” containing 54 models of different ethnic backgrounds for its Fall 2018 collection, exemplify the inclusivity trend. Diesel’s Go with the Flaw spearheaded the celebration of imperfection.

In editorial, “we are steering away from ‘classic beauty stereotypes’ and are now focussing on talent with strong, unique looks, and character,” Hedberg observes. Representation of body image has been slower to change, but as Pidgeon notes, both are changing, and that’s “all thanks to the public. Brands give people what they want. People want to see everyone represented in fashion.” Pidgeon says that he has always fought against over-retouching. “It makes me cringe. It takes the realness away from a photograph. I love to manipulate my colour grading, but I hate manipulating skin. I love stretch marks, I love moles, and hair. The more we leave it in, the more normal it will become.”

For Dubbelde, the evolution is extremely positive. “These movements have been incredibly important because they are opening up new ways of thinking and territories for creatives and brands to really think about the customer and the messages being communicated through image,” he explains. “There has definitely been a huge shift towards establishing a more inclusive and diverse story within the fashion business.”

Adler’s work continues to lean more towards fantasy. “My images help create a character for my subjects,” she explains. “Recently, to accommodate the needs of my clients, I’ve also created images that are cinematic, rather than ‘perfect beauty, or perhaps cast my subjects with usual, unconventional beauty standards. I’ve tried to merge the two factions in my work under the umbrella of art. In my work, I portray women as strong and elegant, and as elements of my bold and graphic artwork.”

Fashion shoots are faster, too, because digital has altered the craft of photography. “I was the last year of RMIT to be trained in analogue film and darkroom,” King notes. “I spent the first two years of shooting everything on film. Digital was just coming into the picture. These days, digital has made photography more convenient, but I feel the whole creative process has changed. You used to have to really think about the shot and take time getting it, just to be sure you had the shot on film. You never knew until it was processed. These days when shooting, the client will say that they have it after a round of shots. Back in film days, you’d do a few more rolls for safety, and that’s where you might have gotten the magic shot.”

Pidgeon has only been in the industry for five years. He is enjoying the rapid changes. “It’s what I find exciting about being a fashion photographer – you have to keep on top of it. I’m the most creative when I’m challenged. I think the industry as a whole is super creative at the moment. A lot of people are experimenting and putting out images that are unexpected – nothing like their usual style. Photographers like Georges Antoni consistently surprise and inspire me,” he states.

King, however, has a different point of view. He feels that social media, and Instagram in particular, have killed a chunk of fashion photography’s wow factor. Both King and Aboud have also noticed a shift in style to a more natural style of photography, minus the “heaven flash lighting and glam model,” King notes, and with a more “pared-down style with a creative colour palette,” Aboud adds.

For King, the wow factor in fashion photography is seen when photographers try to do something different. The wow factor photographer is not afraid to stick to his or her own style. Both of these, he says, are few and far between. “I see so much imagery every day on Instagram, that I feel it’s numbing my sense of seeing a unique fresh image. Lots of it looks similar,” he says. Dubbelde sees the value in social media as a new platform for creatives to be able to share their work and be discovered. “It also gives instant access to content in live time,” he adds. “Only a few years ago you would have to wait to purchase a magazine to see the latest trends from the runways around the world, but now with Instagram and social media you are able to watch this almost instantaneously.”

Video advertising and content are growing at the expense of print in many categories of brand marketing, including fashion. “I love video. I often do it for some of my clients,” King says. But I have also seen clients do a video and spend all that money for one to three assets. Some of them have realised that if I shoot stills for the same budget, they’ll have fifty images to use. The need for more content has some of these clients spending more on stills and sometimes dropping film to meet budgets. I personally think film is a beautiful addition to brand imagery though. There’s nothing like a bit of moving imagery to tell a story and give a campaign another dimension.” Hedberg adds that several of her mainstream clients are trialling video content for advertising and marketing. “They haven’t necessarily seen the return,” she says, “so the focus and budgets have been brought back to the stills component, and the video is treated as an add-on. I do believe that the need for motion content will only increase when we figure out how best to implement it for brands.”

Pidgeon is a fan of fashion films. “I really enjoy what Diesel, Gucci, and Levi’s, in particular, have been doing. It hasn’t changed any budgets in my world, but it is requested a lot more and I will work with the video crews to shoot campaigns at the same time. My fiancée, Lucy, art directed and created the latest Bonds ads, Join The Queendom, and Gotta Be Bonds Coober Pedy commercials. That’s just bragging really, but they’re amazing. I stay away from motion myself. I leave it to the professionals. They don’t need me taking their work, just like I don’t want them to offer stills.” Video reignited a creative spark in Aboud. “My field of expertise has changed,” she says. “I’m now directing film. My short documentary, A Close Shave, shows the vulnerability of three men as they discuss a close shave with life.”

Me too, we too, you too

Aboud’s documentary has a connection to the Me Too movement, which has disrupted the Australian fashion industry less than it has overseas, perhaps because the wild extravagances of power, the outré lifestyles, and the allowances made for “artistic temperament” never flourished with abandon here. “I know what it’s like to be discriminated against,” Aboud states nonetheless. “I started photography at a time when there were very few, maybe two, female commercial fashion photographers. I simply got on with it.”

For Dubbelde, Me Too has been a powerful catalyst to initiate a dialogue around many issues in the world. “It has unearthed wider toxic cultures that have existed for a very long time. I have an immense amount of respect for all the people who have come forward to share their experiences and started to make a change for the better.” Hedberg adds, “I have had quite a respectful experience in the Australian fashion photography scene. However, as a young woman I have definitely been exposed to unsolicited comments of a sexual and derogatory nature. As we move forward, this is happening a lot less as a result of the Me Too movement and the important conversations that followed, particularly in our industry. We still have a way to go, but the change is happening.”

Trevor King applauds the flushing out of any misconduct by photographers. “They should be held responsible for their creepy actions. On the other hand, I see the result of everyone getting a bit too PC when it comes to work. This narrows the chance for people to express themselves without being criticised. I feel as though there is a line that must not be crossed, but that line’s position is subjective and varies from person to person.”

There is talk in every creative industry about the glories of days gone by. The heady days of advertising in the ‘50s and ‘60s. The glamour and gloss of fashion in the ‘70s and ‘80s. The hand-crafting of design before digital. The grass is always greener. “I had an interesting conversation with a photographer who has been in the industry for decades, and I asked if he missed ‘the golden days’ of photography in the ‘80s and ‘90s,” Hedberg recalls. “He did not agree with that statement at all. He said that we are currently in the golden days of photography, and that it has never been as democratic as it is now. And I agree. We are no longer restricted by unattainably expensive gear, or our connections to editors to have our work seen. We are free to express ourselves and to share our work in ways we never have been able to do before.

“Independent media is on the rise and the established media are putting more resources towards digital publications,” Hedberg continues. “Several of the magazines I work with are using both print and online platforms to publish content, and, as a result the ‘image-makers’ have much more opportunities to produce creative work. It is an exciting time. Print magazines are restricted to their number of copies and location, while online editions can have a reach of millions. And it is no surprise that brands have started to advertise in these online spaces, as well as placing targeted ads on social media platforms,” she says.

There is no doubt that fashion photography has changed in the last few years. It had to. Fashion had to, and fashion photography is how the industry is seen. There is little doubt that the change will continue. No industry has the luxury of staying the same, or even evolving slowly these days. Faster, leaner, more responsible, less frivolous, more integrated into real world issues…more of it. These are the imperatives now. The next story on fashion photography may well be different. That, in no small measure, is up to all of you. Create the future.

Contacts

Michele Aboud

Lindsay Adler

Luke Dubbelde

Tintin Hedberg

Trevor King

Ren Pidgeon

Get more stories like this delivered

free to your inbox. Sign up here.