For thirty years, Chris Rainier has worked to preserve languages, indigenous cultures and the knowledge held by elders in traditional societies. His work is a race against time and the forces of change. He spoke to Lyndal Irons before arriving in Sydney for an exhibition, talks and workshops during the 2014 Head On Photo Festival.

As Ansel Adams’ final assistant, Chris Rainier had an enviable photographic education. But one comment his teacher made on the evening of his death would resonate the longest.

“Where has all the time gone? I barely got started...” Time was up that night for the man who had already contributed so much to the field, but it would become an obsession for his assistant, who has, to date, spent over three decades on a mission to preserve traditional cultures on the cusp of change. His pictures carry the minute attention to detail and beauty learned from his time with Adams, but also take on an anthropological, documentary agenda.

A National Geographic Fellow and a leader in his own right today, Rainier has worked for TIME, LIFE, New York Times, Smithsonian and The New Yorker, amongst other titles. His interest in protecting language and culture has led to a number of cultural preservation initiatives, as director of Last Mile Technology Connect, co-director of the Enduring Voices Language Preservation Project, co-director of the National Geographic Society Cultures Ethnosphere Program and director of the Society’s All Roads Photography Program.

His impressive career has been guided by those words of his mentor. “For a lad of 24, [the words] sank very deeply into my psyche,” Rainier says. “It still forms the way I go about work today. Each moment is precious. Each year that passes includes the ability to accomplish something and I see the work I do as a race against time.”

Early life

His upcoming visit to Australia as a headlining guest of the Head On Photo Festival is a return to a country he grew up in. Rainier lived in Melbourne from 1962-68 while his father, a keen amateur photographer, worked in the oil industry. It was there he first held a camera in his hands, and the enthusiasm for the instrument was passed on from father to son, who also encouraged an appreciation of the outback and other isolated places. “My father is South African, so I also spent a lot of time in the wilds of Africa,” recalls Rainier. “Many of those experiences informed my connection to the wilderness and indigenous cultures.”

After formalising his education in photography at university, Rainier undertook a workshop with Ansel Adams, shared a rapport and became his final assistant. Under Adams’ instruction, his real education began. “Obviously on a technical level, it was like getting a PhD in the photographic process. But I think meeting him and being within his life during his final five years...there were a tremendous number of people who would come into his life. Not only the world’s top photographers, but also musicians, politicians and artists of all kinds.” Rainier accompanied Adams to Yosemite and his home in Big Sur, taking it upon himself to create proofs of close to 50,000 negatives that Adams made over his entire career. “I used this as a teaching tool for myself, starting with his very first negative. I started to understand his photographic process, the process of failure, success and evolution.”

He credits his time with Adams for expanding his awareness of how art can be used as a social tool to persuade and shape people’s perspectives. But while Adams was concerned with landscape and conservation, Rainier knew he wanted to include people in the frame, to raise awareness of traditional cultures and practices potentially threatened by change.

He worked for National Geographic, but also the United Nations, International Red Cross, and as a contract photographer for TIME magazine, stationed in Bosnia, Rwanda, Somalia, and Ethiopia. “I covered September 11 in the States and the first south-east tsunami. But as a backdrop to that I was doing very personal work. Ansel once told me that there are assignments from within and assignments from outside. The exterior ones pay the bills and motivate you on a certain level. My personal work can be seen in some of the books I’ve done. There has been a dance between my two types of work. Once I left the Ansel Adams studio, I had my mission carved out. I knew where I wanted to go and I continue to do that.”

Resisting classification, Rainier describes himself as “almost schizophrenic” in his habits of jumping from hardcore photojournalism to fine art, to almost anthropological documentation. “Whether I am sitting on the most beautiful island in the Pacific or whether I am in the middle of a war zone, I am there photographing and present in the situation. I use my camera as a passport to the human experience, and for me, photography is a journey into the four corners of the human experience: from the darkest we are capable of, to sublime moments of generosity and compassion. For me, taking my camera into both those experiences is important.”

One foot in The Garden of Eden

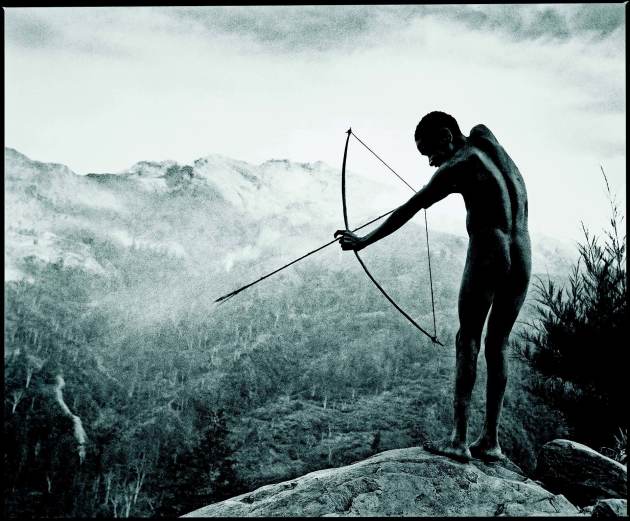

Rainier spent time in India and in Tibetan monasteries, but it was New Guinea that inspired a ten-year project which saw him spend half of each year away from

home. “Growing up in Australia, my father had often spoken of this exotic land north of us where there were still cultures with one foot in The Garden of Eden,” says Rainier. “I first had the opportunity to go there in 1985 and I fell in love with it. It epitomised so much of what my mission was about. There is this amazing moment in human evolution right now where we still have a number of places around the Earth where people live in a very traditional way. That may not last forever. I feel a strong obligation to document, archive, preserve and maintain that for future generations.”

In another series, Ancient Marks, Rainier spent eight years exploring tribal markings and tattooing in both contemporary and traditional cultures. Through shoots with subjects ranging from remote indigenous tribes to the Yazuka and American gangs, he found a renaissance in modern societies, people searching for meaning and initiation, using their bodies as a canvas.

Though he still actively photographs his own projects, Rainier has become equally concerned with empowering people to tell their own stories. His work with the Last Mile Technology Program equips indigenous communities to communicate using the

latest technology. He says the work of the program is difficult to describe with a broad brush overview because each culture has different motivations for engaging with technology. “People access [Last Mile] for very different reasons,” he explains. “We are working with a group of Sherpa on the base camp of Everest and down below. Climate change is affecting people right across the Himalayas, creating these unnatural lakes of melted glaciers – unnatural in the sense that they are building up rapidly and could break at any moment. Sherpa communities are deeply concerned about all their villages downstream. We are trying to get the technology for them to have a voice around these issues – something to add to the mix of Western scientists. We are also dealing with tribes in the Peruvian Amazon jungle and we are working with women’s co-ops in Botswana. There’s a variety of different needs that come up."

Rainier is fascinated by the creative ways groups want to use technology, and the increasing number of people coming online to be part of that dialogue. “They talk about the Internet truly connecting everyone, but it is far from that,” he said. “If we are not careful, we will leave the vast majority of the world’s population behind. It is always a tricky conversation around bringing technology to traditional cultures. It smacks of a conversation that we are changing them, but I think there are very few places on the planet now that won’t very quickly be connected and I think it’s important to allow people to have the right tools. Information is power and many traditional cultures want access to information, to job opportunities, to language preservation opportunities, to medical opportunities.”

Because of the risk of changing the very cultures they are trying to preserve, Last Mile works on an invite-only basis. Rainier is keenly aware that not all cultures are interested in preserving their traditions. But many desperately want to record their own stories, languages, and knowledge of their elders, or fear being left behind in the digital divide. “That’s where Last Mile is working,” Rainier says, “in that space where people are asking for some help. We offer cameras, computers, tablets, smart phones, and a little training in storytelling. Around 80 per cent of the 6,000 languages spoken in the world are traditional. Mainstream languages are just the tip of the iceberg. But, of those 6,000 languages, most are oral. Storytelling is the transmission vehicle, so many traditional cultures are visual in their story telling and they are stunned and excited about seeing a universal language – photography. I think technology allows us to add more chairs to the table, so to speak.”

Rainier’s highly-wired eight-year-old son makes him aware of just how rapidly humans are adapting to new technology. “We are all just getting a grasp of this revolution, let alone the impact it has on traditional cultures. I am hypersensitive to this. But I am also not the decider. People are asking us to bring them the technology. We are facilitating a process that’s already underway.”

Keeping culture

Upon returning to America, some things about his own culture appear strange after an assignment, such as an intoxication with moving faster and accomplishing more. “I think we’ve mistaken quantity of information for wisdom, and wisdom is always what I seek when I’m off the bandwidth of contemporary modern culture. Stepping back into the traditional means slowing down, and it’s in the void between experiences where I learn the most. Whenever I jump back into Western culture, I enjoy it, but it moves rather rapidly and I lose something in the process.”

There are places that haunt him, like Libya, that he’d love to get to, and the fact he can’t preserve them all as they change daily. “Sleep is optional – there are so many things to document,” he says. “Anthropologist Margaret Mead once said her greatest fear was that having been born into a polychromatic world, that suddenly we’ll wake up in a monochromatic world and that no one would know there was ever any difference. Eventually we will become a global culture and I think we’ve even seen it in our lifetime how quickly things become efficient, and therefore streamlined and homogenised. That is the beginning of the process of breaking down culture.”

The key to documenting a culture well, is time, but time is limited. “I’ve seen places change so rapidly, so I do feel pressure. I’m not saying cultures can’t change or that they should remain the same. My personal mission is just to be there in the moment before change happens. I think those are the moments we’ll cherish for many generations to come.”

Contact

chrisrainier.com

lastmiletechnologyconnect.org

headon.com.au