Q&A Ken Light

Documentary photographer Ken Light is both an observer and a storyteller. He enters the worlds of his subjects and documents their realities to give us a momentary glimpse into their lives. Likewise, Capture got a glimpse into his career and approach to photography.

Documentary photography differs from similar crafts like photojournalism, in that it tends to focus on long form projects. Photographers will find a subject and follow the story for months, or even years at a time. Starting out documenting student activism in America, Ken Light developed a keen interest in exposing many of his country’s shortcomings. His past projects include men on Texas death row and the passage of illegal Mexican migrants across the border, amongst many others. He has produced a multitude of books compiling his photographic works. He is currently the Reva and David Logan Professor and curator at the Graduate School of Journalism at the University of California, Berkeley. Light is also the co-founder of Fotovision, a non-profit organisation which generated a community of photographers to support their documentary peers in creating, editing, funding and distributing a body of work.

Capture: What drew you to a career in photography and documentary photography?

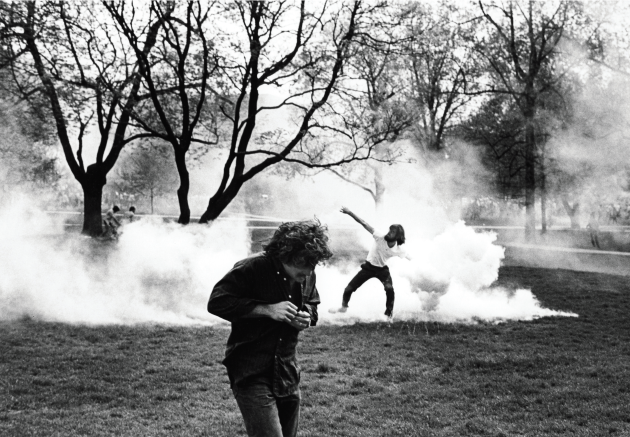

Ken Light: I was 18 and a college student in 1969 when I started. It was a very tumultuous year in American history with protests against the war in Vietnam on college campuses. I was active as an organiser against the war and I frequently had a camera with me. As I was organising, I would often bring my camera with me and I began to photograph the things around me. That seemed like a more successful way to have a voice, to tell a story and to show things that you thought needed to be seen. April of 1970, President Nixon secretly bombed Cambodia, and all of the campuses throughout the United States rose up in protest. There were massive demonstrations and riots. Four students were killed at Kent State University by the National Guard, trying to stop the students from protesting. About five days before those students were killed, I was at Ohio State University, where there was a massive riot. I made photos and was arrested while taking the photographs. When I got out of jail the next day, I developed the film and the pictures were published all over the world. As a young photographer, just starting out, not even understanding what photography was about, it was a powerful message that you could have a voice, that photography could be a way of telling your story, of seeing the things around you. And that propelled me forward.

Capture: How has documentary photography and the photography industry changed since you first started?

Ken Light: When I first started, it was completely black and white, it was in the darkroom, developing films, making prints, sending prints for people to use. There were many different photo agencies that represented groups of photographers. That’s all changed now. Now, almost no one is using the darkroom – except for me! I’m still shooting film and printing in the wet darkroom. There are fewer photo agencies. There are mega agencies, like Getty and Corbis, that dominate the market. When I started in the early 1970s, some major magazines, such as Look and LIFE magazine, were just finishing up. But there were lots of other places to get your photographs published. And for me, as a young photographer, there were all these underground, alternative newspapers that were put out by young people. Almost every American city had an alternative newspaper and that was a great way for your photographs to be seen, and published, and they were writing stories about the other side of what was happening in America. Most of those have disappeared, so the whole landscape has changed.

Capture: How can emerging documentary photographers survive and thrive in this new world?

Ken Light: If you look at the history of photography, from when documentary photographers first emerged, like Thomas Annan, Lewis Hine or Jacob Riis, it was always hard. It was always hard to do stories and it was always hard getting work out. So I think in this new age, it takes the same persistence, it takes the same passion that one has to really feel a story is important and really has to invest their time and energy in seeing that story and making photographs. It’s definitely harder to make money, and this is of course a problem. Crowdfunding sites like Kickstarter and Indiegogo, are really amazing sources that a lot of documentary photographers are using to raise money for projects and books. That was something that didn’t exist in the past, so that’s really positive. The Internet is an amazing opportunity for people to show their work. The problem is how to get money from that? How do you support yourself as a photographer?

Believe it or not, when I started out as a photographer I worked in a factory, packing clothes and t-shirts. Then I worked as a graphic designer three days week so I could have four days where I could photograph. The path of doing documentary photography is really a lonely path in the sense that you’re not being hired by a magazine or newspapers. Because even in the 1970s when I started, Newsweek or Time or other publications might send you out for three or four days, but the tradition of documentary photography is that you spend months or years working on a project. And that’s something that almost no one will support financially. You just have to find alternative ways of making money to support yourself and then invest in the projects that you’re doing.

Capture: Your projects often cover a specific subject very in depth. How do you get funding to support you completing these projects?

Ken Light: I’ve been really lucky that I teach. I actually get a pay check at the end of every month, so that really helps. I chose to teach early in my career. I felt that to really invest time into a project, there were going to be no clients or magazines that were going to say to me “We’re going to let you go out and spend four years working in Mississippi,” or “Yes, we’ll pay for you to go to Texas death row to photograph.” There were people who were interested in the end result, both as books and as short essays in magazines, but to get someone to actually pay you over many years just wasn’t possible. So for me, it was teaching. Any additional income I made shooting commissions for clients, magazines and non-profits would then be reinvested in my projects.

Capture: As a documentary photographer, the stories you capture often have a major emotional impact. Which project has influenced you the most?

Ken Light: I think each story that you do teaches you something. One moving project that I did was a project on Texas death row. A couple weeks ago, I actually did a count of the men that I photographed, and almost seventy of the men that I photographed have been executed since I did that project, which is pretty incredible. Knowing you’ve met these men, and you’ve talked to them, and photographed them, and learnt their stories, and then they’re executed. But then on the other side, you realise that a lot of these men are not nice. They did horrible crimes. There are victims’ and families’ lives that have been destroyed. So that was a particularly difficult project, just emotionally, knowing that America has this barbaric practice of executing people for crimes. Having the responsibility of being allowed inside to make photographs and knowing that very few people have had this opportunity, there’s a lot of pressure. There’s a lot of emotional angst that you have about doing a good job; really trying to tell the story and figuring out what the story is.

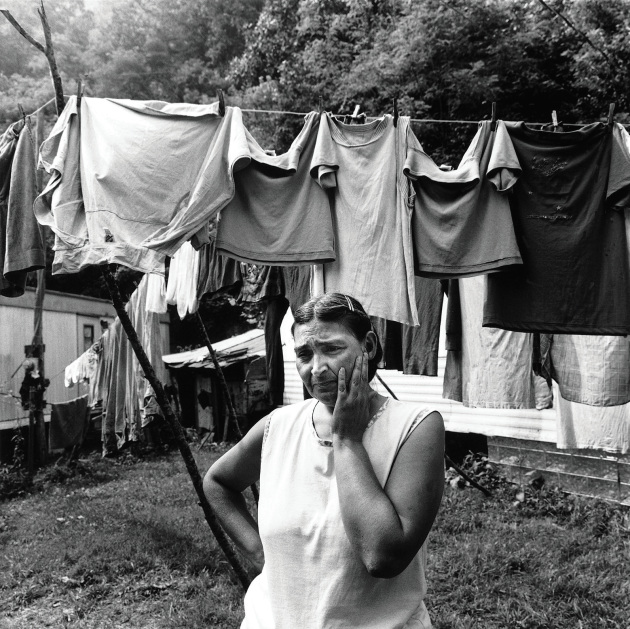

I did a book about Mexican migrants coming into the United States illegally over the border. And that was also very hard to watch and to photograph because you realise these people who are coming from very poor, rural villages in Mexico and they’re coming at night trying to avoid the border patrol and all they want is to have a better life for their family. Most of them are not criminals; they are people who just want to feed their families. They’re people who want to have a better life for themselves. So that was really hard to watch and to photograph and to realise how lucky you are to be on the other side of that.

Capture: How do you choose projects and why?

Ken Light: Sometimes I see an article in the newspaper and I’m shocked, and I can’t believe that something is happening. Sometimes people tell me stories. And sometimes they’re unexpected. There are all these different ways that I tell stories. I think that documentary photography is for curious people. We’re interested in how the world works, and for me how America works. All my work has been in the United States. That’s partly because I’ve always thought that the United States tends to point their fingers at every other country in the world and tells them to ‘shape up’. We have a lot of problems in this country that Americans don’t want to look at, so that’s something that’s always interested me. How can we tell other people how to behave when we have so many social issues in the United States? And part of what I’ve done in my career is to try to look at those issues, try to put a face on them and to engage around those issues.

Capture: You’ve started the non-profit organisation Fotovision. What were your reasons for starting this?

Ken Light: We aimed to support photographers worldwide. The idea was to create a community of photographers interested in documentary, to train the next generation, to bring important people to talk, and to carry the torch. I think it’s the responsibility of those of us who have been doing this for a very long time to make sure that there’s a new generation who will continue, who have some understanding of the history of documentary, who understand the passion of what it is all of us are trying to do, and to carry that forward. I think part of it, is that photography is difficult to do now, so to give that support to younger photographers and to inspire them was one of the great things that came out of Fotovision.

Capture: How important is formal education in documentary photography?

Ken Light: Different people have different ways of learning. For some people, going to school is an incredibly important experience. There are many doors that are opened up and they work really well in that environment. But for others that environment is not so good for them. They are better off learning on their own. They are better off going to lectures, finding a mentor to work with, maybe doing an internship with a photographer and looking at photographs. There are many paths and a young photographer really needs to figure out what works for them. I think the good thing about going to a college or university is that your friends who are photographers look at your work and inspire you. One of the greatest things about going to school is that you have a community right there. If you’re doing it by yourself, it’s harder to find that community of support.

Capture: What part does failure play in becoming a success? And what are some of the most important lessons you’ve learnt from your failures?

Ken Light: Failure can be hard, but it can also be good. I think documentary photographers working on projects are a very stubborn group of individuals. We get an idea in our head, we decide that we need to move forward and we need to do that project. It doesn’t matter that people tell you no one cares. So I think being stubborn is important. Having failure is important. It pushes me forward to prove that my voice is important, to prove that what I am trying to say is important. I guess it kind of stiffens your backbone. Over the years and decades, you realise that if you work hard and create a body of work that it will go out into the world and people will see it. Failure’s not fun, but you can’t let it stop you from what you’re doing.

Capture: How do you think success is measured in your field?

Ken Light: I think traditionally people look at how many books you have, how many shows you have, how impactful your photographs are. Those are the standard things that people are looking at. But I really think you must have your own standard. If you look at the history of photography, photographers tend to be way ahead of what people are thinking and they’re doing stories that no one’s interested in. Sometimes people won’t be interested in it for ten, twenty or thirty years. Somehow, many documentary photographers have their fingers on the pulse of their own world and often they are way ahead of what people are talking about or what they are interested in. So I think you have to really believe in your own voice. You have to really believe that what it is you’re trying to say, what you’re trying to see, and what it is you’re trying to share though your photographs, is important. I think, for me at least, if I can make a really good photograph that really expresses something that I felt at the moment I pushed the shutter, then I feel like I’ve succeeded. It’s really personal in a way.

Capture: What advice or suggestions do you have for other, newer photographers that want to advance their careers?

Ken Light: I always say the hardest thing is to get out the door. You may be thinking about doing a body of work, but don’t think too long. Take your camera and get out and start shooting. Really dive into it. Get out, photograph, don’t give up, but also appreciate that some people around you may not think what you’re doing is important. Remember, it’s our job as documentary photographers to create work and create stories that enlighten the people who look at our pictures. Set a goal for yourself and try to stick to it.

Also, you always have to think about the person who’s going to look at the photograph. You want them to be drawn into your subject, the people that you’re interacting with, who are allowing you to enter their lives. So chose a subject that you’re passionate about, set a goal, set a number of photographs, a timeframe, and push yourself to grow. Push yourself to work outside your normal boundaries; work outside the box that you’re in. Think about your work as making a statement about your world. Understand that the power of the photograph is to witness the world around us, which is ever changing. Realise that in 10, 20 or 50 years from now, you’ll look back at what you’ve done, and you want to make sure that while you’re doing it now, you’re pushing yourself as hard as you can. If you do that, you’re on your way to reaching out with your interests to tell an important story.