Ron Haviv

While he recognises the limitations of photojournalism, Ron Haviv also knows its strengths. The veteran conflict photographer tells Anne Susskind how he finds his balance and stops himself minding when cat videos get more clicks than wars.

Photojournalism is powerful, but it cannot stop a genocide, says Ron Haviv, who has covered three – in Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur – and seen people executed, up close. Sometimes, when he sends shocking imagery out into the world and nothing changes, he’s felt as if he has failed. But, says Haviv, photos have ‘many lives’, and later it becomes apparent what photography can do, not only what it can’t. Haviv, who has documented over 25 wars and conflicts since the late 1980s, says that it’s about understanding limitations.

© Ron Haviv/VII Photo.

“Especially in the west, and especially as Americans, you think it’s everything or nothing. I felt that if the work had no impact, I couldn’t keep doing this. But then it starts to become a little more feasible… if we can push someone somewhere to be educated about the world, or possibly vote, or say something to a politician representing them, or even simply donate money to Doctors without Borders or UNICEF,” he says. “The thing about most people is that their actions rarely affect anyone outside their immediate circles of friends or family. Having spoken to people who’ve said the work made them break out of that circle, it’s a real tribute to the power of photojournalism.”

Compelling evidence

In Bosnia, for almost four years, journalists were there day in and day out, but there was no immediate reaction; a bit like what’s happening in Syria now, where people were doing a little of this, a little of that, but not really galvanising. “It fails in that way, but at the same time the work myself and colleagues have done covering the refugees, for instance, shows it’s had an impact. Look at the Kurdish Syrian child on the beach,” Haviv says. “It didn’t change the exodus, and didn’t stop the war in Syria, but it changed the conversation. I am absolutely realistic about the limitations, but at the same time, what are the other options?”

Haviv’s work in Bosnia is currently being used on the international stage, as evidence in the trial of the Bosnian Serbian political leadership in The Hague Tribunal, and has also been instrumental in several different trials and indictments in The Hague and International Committee for the war in Yugoslavia (ICTY). In Bosnia, he was “fortunate, or unfortunate” enough to be with the Tigers, the Serbian paramilitary, before the official start of the war. “I was with them when they were executing some middle-aged civilians and was able to document some of the atrocities. Some of the work I did around Srebrenica and the prison camps also related to human rights abuses.”

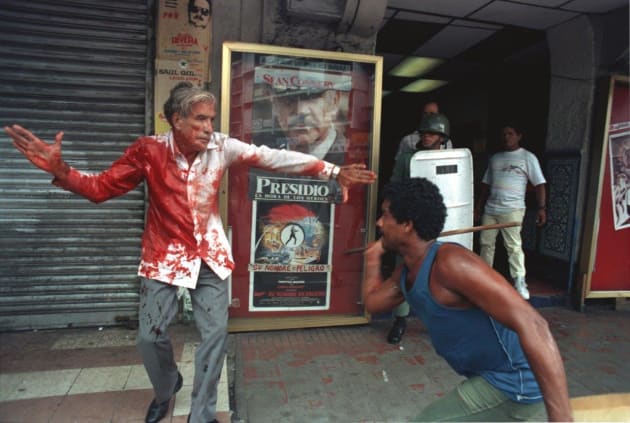

Going back, his early photos from Panama in 1989 were used by President George Bush in his address to the nation as one of the justifications when the US invaded to topple the dictatorship.

Camaraderie and luck

Haviv, who is visiting Sydney in April for the Head On Photo Festival, did not even set out to become a photographer, and definitely not a conflict photographer. It was not about noble intentions. His photography and where it has taken him is what politicised him.

When he was young, he had intended to be a writer. But a gift of a camera, and a friend for whom photography was a very serious hobby, drew him in. Working first on the business side for fashion and portrait photographer Francesco Scavullo in New York, to help pay for university, and later for free as an intern in New York, Haviv entered “this amazing world of camaraderie” of people trying to make a difference, in a very interesting way, through travel.

Then came a lucky break. It was 1989 and Haviv was 23. “The first foreign story I went on was covering the Panama election. I’d met a photographer, Chris Morris, on the streets of New York. He was more experienced and had come back from overseas, working for a magazine. I asked where next, and he said Panama. At that point, I had no idea where Panama was, but I thought if this guy was going to Panama, that’s the place to go. I said, ‘See you there’.”

Haviv convinced the New York Post to send him, but then management changed and all travel was cancelled. “I happened to run into Chris within hours and he said ‘Oh, I have had an extra plane ticket and I’m on assignment for Time. You’re welcome to stay with me. I have an extra bed in my room, an extra seat in my car. Basically, Chris gave me the trip; it was totally amazing, and very generous.”

Given that Haviv wound up with the cover [of Time], it wasn’t the best of outcomes [for Morris], but he and Morris spent the next couple of years working together. Along with Haviv, Morris, “one of the best photographers in the world”, is one of the co-founders of VII, their photographic agency, in New York.

The big wide world

At the time, the “big deal” photographically for Haviv was getting the cover. It set him on his path. But the real historical significance became apparent six months later when the President referenced the photographs. For Haviv, it was an epiphany, a pillar and a foundation in his understanding of what he was doing, and what photography could do.

As well, it was 1989 and the world was changing dramatically. His success in Panama was his entrée. He photographed the wall coming down in Berlin, went to South Africa the following year, and then came the liberation of Kuwait City. In 1990, he was in Haiti for the first democratic elections, and after that, Yugoslavia. “I started to understand extreme situations where the future of a country is determined. Countries are born and countries die. Things often happen in times of violence, and often in those times, there are many stories that need to be told the most; and most are never told.”

There’s no shortage of conflict and human rights abuse to choose from. A mix of things determines where Haviv goes: with Yugoslavia, he was there at the outset and returned over a decade, determined to see it through. With other places, for example Haiti, where he worked for 20 years, perhaps it was that he liked the people more or found the stories more compelling. Sometimes, it’s as simple as whether he’s got funding, or what he feels he can bring to a situation. He is, he says, “absolutely fortunate” for several reasons: that he’s still here in one piece – when several friends have been wounded or killed, and to see history unfold and have the privilege of showing the world his interpretation of what he sees. He’s been arrested many times, taken prisoner several times, and had his camera and film taken (by people possibly ashamed or humiliated that the world should see what’s going on in their country). “[Getting the images and ensuring they get seen] is a continuous fight many people such as myself have had, and continue to have…” So you need to be brave? “You need to be smart at times, which can be construed as being brave, but being smart is also running away.”

People often ask how his work has changed him. But, as he replies, we’re a product of all our experiences, how would he know what he would have been like had he been, say, a lawyer? What he does know is that if ever he has no emotional reaction, it’ll be time to move on. “While I’m not necessarily breaking down and crying in the field and unable to work, I have to find the balance between that emotional connection to what I’m seeing and being able to function. I want my reaction to come through to the viewer, so I try find my balance.”

Digital world, digital war

It’s the 15th anniversary of VII this year, and the agency has grown from seven to 19. In the late ‘90s and early 2000s, Mark Getty with Getty images and Bill Gates with the Corbis Agency began buying up photo agencies because images were becoming very valuable. Haviv and six other colleagues who wanted control over their photographic life, from the business to the publication side, took their lead from Magnum, the photographic agency started 50 years earlier, and created an agency for digital times. Many other small agencies have emerged subsequently.

Afghanistan was the first completely digital war. “In Kosovo, we were shooting film and scanning it with scanners in the field and sending it on satellite phones. But by the time Afghanistan happened, because of the location and lack of infrastructure, and the quality of cameras, digital was the only way for us to get our work out. People did shoot film during the war, but no-one saw it in real time because we were so far away from everything.”

Haviv was with a small group of journalists living on the frontlines around Kabul with the Northern Alliance fighting the Taliban at the time. Without one-hour photo labs, a decent quality of water and with the dust so profound [which affected the negatives], it didn’t make sense to even try use film. All the camera companies were competing and, in the time he was there, technology moved so fast that the camera he arrived with became obsolete twice. Photographers were arriving with cameras twice as good as three months earlier. Working completely digitally, which he now does all the time, is very different. To see work immediately and get it out straight away through satellite phones was a very new experience, as was communicating in almost real time.

Cell phones changed things even more later on, with everyone able to access everything, almost everywhere, straight away. Because often the photographer is still in place while the work is published, relationships change. Social media heightens the power of the image and in certain cases, rebel soldiers,

government officials, public affairs officers, and those from the American (and Australian) military have begun trying to take control in a way they never had before.

There have been other changes, he says. Photography and writing are two different story-telling methodologies and having a good writer and photographer working together creates a great synergy – one capturing the immediate image, the other able to return and ask more questions. Being alone is more difficult, but more common now because of financial realities.

Through the 1990s and early 2000s, conflict photographers were a small group who’d see each other everywhere. Now, with the collapse of the financial support system for magazines, that’s no longer the case. As well, because of technology and the low cost of cameras, many local photographers create great work. “Now we have Syrian photographers documenting the world around them, and Libyan photographers whose work we never would have seen before have their work on the same playing field as mine or other internationals.”

The need to diversify

While technology has opened up the world for young photographers, they have to understand it’s a business and make proper decisions based on that, even more so as they get older and there are other expenses and life responsibilities.

Often, Haviv’s conflict work doesn’t pay at all. “I wouldn’t call it lucrative,” he says. “Many times I’m paying my own way, hoping to recoup the money at the end. I think one of the ways to survive today as a photographer is to diversify and have other revenue streams coming in.”

Haviv also works in advertising, with American Express and IBM, for example, both for the challenge and the revenue.

Recently, he’s done an anti-meth advertising campaign which he found interesting because it was both socially relevant and “completely creative”. The people used were models: “I created everything about them. That campaign has had incredible success in reducing meth use among teenagers, and probably that campaign – versus spending time with a real meth user and having a photo essay in a magazine – has had more impact.”

He’s not disheartened either by how his work gets mixed up with cat photos and videos, or when pictures of refugees appear next to somebody’s lunch, or what they did last night. “Of course the cat video has the most likes. But that doesn’t mean that this work shouldn’t be done and that it’s not having an impact. Part of the photographer’s responsibility is to try to photograph that story differently so it stands out, and that’s your skill as a visual journalist - to have the way you approach things rise above the other voices. Those photo don’t die, they have different lives.”

The Lost Rolls

The Lost Rolls, the multimedia exhibition he’s bringing to Australia for Head On, is “referencing the end of the analogue era”, and is about memory, and understanding how photography works with memory. For the project, Haviv developed over 200 canisters of film in 2015, taken between 1988 and 2012, perhaps with a second or third camera.

Photos have emerged that he doesn’t even remember taking. “I’d always expected that when I saw a photograph I took, I could tell you where I was that day, that it would be a sort of trigger. Here I was looking at photos that I knew were mine because I physically had them, but I couldn’t remember locations, dates and even people that seemed to know me, and were posing. “Having not seen it in a certain period of time, I’d lost the ability to create this memory foundation, so not remembering it is about growing old, and obviously my own memory.”

Many people over a certain age have memories locked in these little canisters, undeveloped from, say, Christmas 1990, or Thanksgiving or a holiday or wedding, but the relationship between photographer, subject and the physical roll of film is ending because so few people use film. The idea of unknown images is ending too, with the end of analogue. Today, most people work with their phones, so have, at the very least, the place, date and time the image was captured.

“Basically for me, as I was looking through all this work, I was having some incomplete memories completed and thinking, ‘Oh my god, I was looking for that image’, or ‘I remember now what happened that day’ and everything kind’ve comes together. Also, there’s very interesting imagery of situations where I had photo stories that were very well known and here was a different angle, locked away.”

In a series with the gangs in El Salvador, his memory had frozen into one 35mm widely published photo of gang members being arrested. Then, in a different format, suddenly he was looking at a panoramic version of that same image. The negative was damaged from colour changes too, so it was “from that scene, but not from that scene.” Memories once broken are now complete, while memories once complete are now broken.

In another commentary about time, he said, the photographs and the film itself are damaged because of light leaks, and mould, and so on. Just like us? “Exactly… and that was also very disconcerting, to see this work basically dying in front of you.”

www.ronhaviv.com

All images © Ron Haviv/VII Photo