Alejandro Cegarra: The photographer is present

Only two years into his career, the Venezuelan photojournalist is no stranger to success. Christopher Quyen gets an insight into his life, work and achievements to date.

“I often think about whether I’m just a vain action photographer, but after much contemplation I’ve come to the conclusion that I’m a photographer in action,” Alejandro Cegarra says. Born in 1989, the emerging, award-winning photographer, still calls Caracas home. Through serendipity, the chance to pursue photography fell into his lap when he was given his first camera. “It was a series of coincidences; my mother bought a camera she never learnt to use, so she gave it to me and told me ‘if you learn how to use it, you can keep it.’ So I suppose that’s how I first got started. I feel very lucky when I think about it,” says Cegarra.

A cause for action

Commencing his formal education in 2010, Cegarra studied photography at the Roberto Mata Taller de Fotografia while simultaneously studying for a Bachelor of Advertising/Publicity at Alejandro de Humboldt University. It was only after spending a year working at Creative Army, an advertising agency, that he saw his hobby of photography transform into a viable profession. In 2012, he began his career in photojournalism finding work filling in for other photographers at the largest newspaper in Venezuela, Ultimas Noticias, which eventually led to a full-time position in 2013. In November 2013, Cegarra also started working as a stringer for Associated Press. These jobs combined with his personal projects sowed the seeds for success in early 2014 when Cegarra’s photography was exhibited in the PhotoEspaña festival and chosen by the Magnum Photos agency as part of the 30 Under 30 contest where he won the Audience Award. He also went on to win third

place in the Sony World Photography Awards in the Contemporary Issues category for his series The Other Side of the Tower of David and was selected as the winner of the Leica Oskar Barnack Newcomer Award in 2014. Achieving this much in such a short period of time, one feels compelled to ask Cegarra just how he does it. The answer to that question is simple: The photographer has to be present.

No time like the present

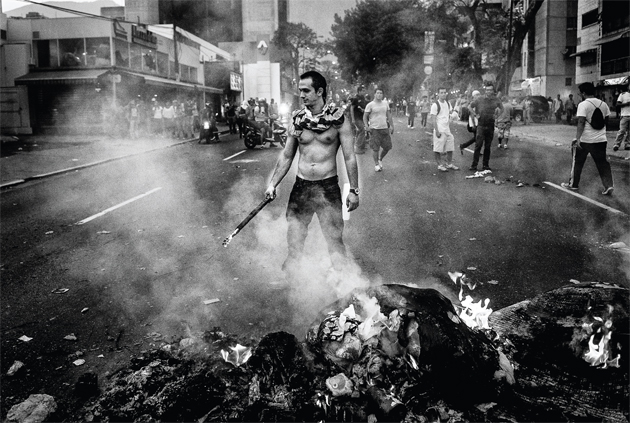

Being a man of presence, Cegarra’s work ethic is reminiscent of a famous statement from the co-founder of Magnum Photos, Robert Capa, who said: “If your photographs aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough”. For Cegarra, being present is the most important aspect of his job as a photographer as demonstrated by his work on the Tower of David and the student riots in Caracas. “I was the most frightened photographer during the riots, partly because I’m one of the youngest photographers in the field. I lack experience and I don’t want to get hurt, but it is my work and I believe my most important duty is to be there. For protection, I wear a Kevlar helmet, a bullet-proof vest and a gas mask. I’m very close to the action partly because I dislike telephoto lenses, despite always carrying one,” he says. Staying true to his work ethic, Cegarra shot his project on the Tower of David on a Canon 7D with a 20mm. For his work on the riots, Associated Press gave him two Canon 5D Mark II bodies paired with a 16-35mm and a 50mm. His next camera will be a Leica M with a 35mm lens.

The jungle of human nature

When Cegarra picks his subjects, he doesn’t limit himself to subjects within his comfort zone. What he is searching for is human nature, which he finds hopelessly unfair. His eyes are searching for the unseen, the human misery of those that are less fortunate. “My attention, my lens, focuses on those that suffer and confront adversity. Those who live in conditions that I myself have never known,” he says. For Cegarra, all these images must come from a place of feeling. “My subjects have to be something that I feel for, or I fear. It has to be something that has made me very angry or very sad. It’s something personal and always related to my feelings. It cannot be another way. Choosing subjects like this has pushed my limits and fed my natural curiosity,” he says.

“The hardest part of being a photographer is when the things you want to photograph are the things that scare you the most, but I believe it has made me a better photographer,” he says. By choosing subjects like this, he hopes that he can give a voice to those that can’t speak. “I don’t know what exactly my message is, but I want to bring some justice to the world. Every time I’m doing a new project, I ask myself, ‘Is this project bringing something relevant to the world?’ It may be a little naïve, but it is my motto,” he says.

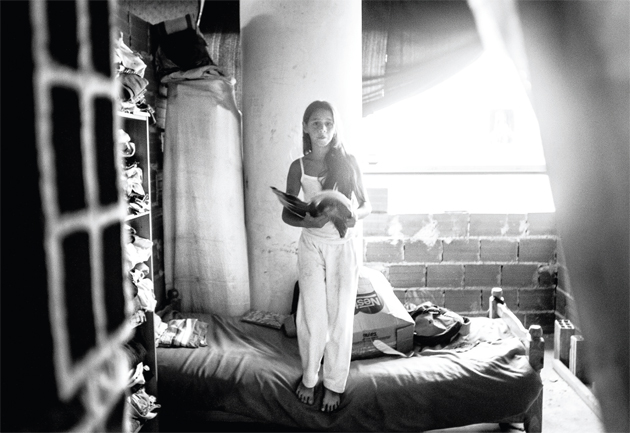

Cegarra’s natural curiosity has led him to his award-winning series,

The Other Side of the Tower of David. Inspired by an unsatisfactory

documentary about the tower, Cegarra knew that there was so much more to explore within its confines. “My first thoughtsabout the documentary were surely that couldn’t be everything; what a waste of such a great opportunity to access the tower. So I grabbed my camera and went to the door of the tower and I started to shout: ‘Hey! I want to take pictures inside!’ It was stupid of me and I wouldn’t do it that way ever again, but it felt like it was my duty to tell Venezuelans that we were wrong about the tower,” he says. After being granted access to the tower, he spent almost five months getting to know the people within. “I walked and talked a lot. I was hungry for their stories,” he says. “I feel like taking photos was the last thing I did,” he says. Spending time to build a relationship with his subjects gave each of his photos an implicit intimacy, and Cegarra can now call a lot of his subjects within the tower his friends. One of his favourite photographs is of a girl, Genesis, studying over her bed. “The picture of Genesis is special because she is the hope inside the tower. She is a beautiful kid in a complicated context; that is what the picture says in that one shot,” he says. Cegarra says that he never captured a similar moment with her like this prior to or after the particular frame.

No more secret identities

Ultimately, Cegarra believes in a coexistence between person and photographer, in that as he develops as a person so too will his photography. “I think I’m a nice person. I’m always thinking that the only way to be a good photographer is to be a good person. My personality is my photography. I love open spaces, the light and the sensation of freedom, and my photos are exactly that,” he says. From the two years that he has watched himself grow from novice photojournalist to award-winning photographer, Cegarra has always taken into consideration his own personal perspective of the world in conjunction with his photography. “I’m more mature, not only as a photographer, but also as a person. Photography has given me a new

perspective of the world and my country, and that has given me new ways to approach more sensitive projects. If I look at my pictures from two years ago, I just see pictures. But if I look at the pictures I’m taking now, I see the soul of the photo and the beauty,” he says. It is clear that the photographic process is symbolic of Cegarra’s thought process. By framing up a shot, focusing and capturing a single photograph, he stares into the face of humanity as a person and then, for a moment, the photographer is present.